This post is part of the New York City Icons series. In the coming months, I’ll be diving into the history of various iconic New York City foods and drinks, in addition to regular Edible History content.

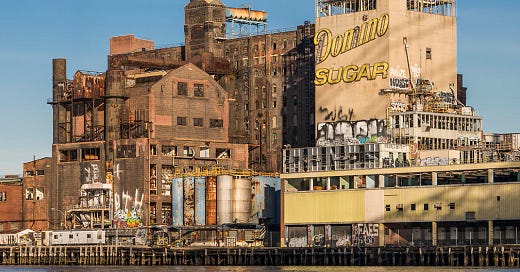

Many years ago I went to a party in the Domino Sugar Refinery. The building sits on the waterfront in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Its iconic yellow “Domino Sugar” sign hanging high above the East River. I cannot recall who hosted the party, how my friends and I heard about the party, or really any of the finer details. We were young, there was going to be booze and live music. We didn’t ask questions.

We hopped on a boat on the Manhattan side of the river, somewhere south of the bridges. A long queue of fellow revelers and a creaking metal ramp, led us to a rather large ferry sized boat. We jumped aboard, excited, nervous. Cool wind lashed about the dark spring night.

At this point the factory had stopped refining sugar years ago. And Williamsburg was not yet the Williamsburg we know today. There were no shiny high rise condos lining the shore. There were no pilates studios, $8 matcha lattes, or outposts of luxury designer stores populating North 6th Street. The waterfront was a tangle of old railway tracks, parts of walls, and piers collapsing into the water. Everywhere shrubs and weeds emerged from the broken concrete. Nature takes over quickly once man is gone.

Once we had made our way inside, we were greeted with soaring ceilings. The place was huge and it was packed. Laser lights criss crossed over the heads of the dancing crowd. We explored floor after floor, all pretty dark, of party-goers dancing, drinking and smoking. It was one of those divine New York City nights when the stars align, a mysterious location opens itself up, for just a moment, to a complete blowout – and somehow you’re on the list (If anyone reading this also attended the Domino party around 2006/2007 and remembers how it even came about – please hit reply and refresh my memory).

When the Domino Sugar Refinery opened in 1882, it was one of the largest sugar refineries in the United States – processing around three-fourths of all the sugar in the nation. And while it certainly wasn’t the only sugar refinery on the Williamsburg waterfront, the family who owned and operated Domino were by far the richest and most powerful: the Havemeyers.

If you’ve been to Williamsburg, you’ve likely walked along Havemeyer street, which runs from Divisions Avenue just south of the Williamsburg Bridge, up towards McCarren Park. This 14 block long street pays homage to a powerhouse family who are surprisingly unknown in Gilded Age lore.

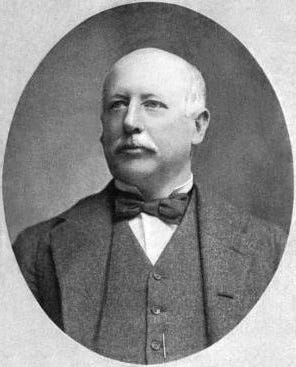

Henry O. Havemeyer, who led the family’s sugar company, the American Sugar Refining Company, during its heyday, was one of the richest Americans who ever lived. We’re talking Rockerfeller rich. Vanderbilt rich. Carnegie rich. Henry and his wife Lousine had an unparalleled art collection: Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Degas, Cezanne, Monet, El Greco and Goya decorated the walls of their numerous mansions, villas and estates, along with porcelain from China, and ancient Greek bronzes. Their collection would eventually become the largest donation ever to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Havemeyer family got their start in the sugar industry back in 1807. The German-born cousins, Frederick C. Havemeyer and William Havemeyer opened a small refinery on Vandam Street in downtown Manhattan, and by the 1840s the refinery took up the entire city block. By mid-century John C. Havemeyer (Frederick C. Havemeyer’s nephew) looking for cheaper and more spacious real estate, moved the family business over to Brooklyn. At the time Williamsburg, and Brooklyn for that matter, were not yet a part of New York City (the five boroughs didn’t join forces until 1898). Williamsburg was recognized as its own city in 1852, having outgrown its bucolic country village origins, merging with the city of Brooklyn in 1855.

The Havemeyers opened their first Williamsburg refinery on South Third Street and Kent Avenue. But rather quickly, they took over a good chunk of the waterfront, their refineries occupying most of the land from the Williamsburg bridge up through what is now Marsha P. Johnson State Park. In 1882 a massive fire destroyed many of the refinery buildings – and what emerged in the reconstruction was the building that still (in part) stands today.

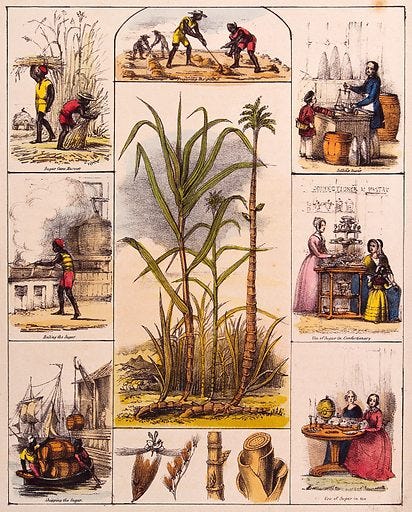

The sugarcane plant comes from Southeast Asia. Medieval Europeans developed a taste for sugar, when it arrived in the West along with other eastern spices (sugar was considered a spice at this time). When Columbus made his second voyage to the West Indies in 1493, he brought along some sugarcane and found it grew quite well. Thus ensued many hundreds of years of utterly horrific sugarcane production in the Caribbean and Brazil. Millions of enslaved Africans toiled in the sugarcane fields, where conditions were so brutal most enslaved people would only survive a few years. Which of course just perpetuated the triangular trade. The West’s addiction to sweetness – for their tea, their coffee, their precious little sweet treats – was fueled by blood.

In his book, The Rise and Fall of The Sugar King: A History of Williamsburg, Brooklyn 1844-1909, Geoffrey Cobb observes the larger geo-political consequences of sugar production in the Caribbean. Cobb writes that Williamsburg specifically refined such massive amounts of Cuban sugar that it transformed, “Cuba into an economic dependent of the United States, engendering a deep resentment that later helped bring Fidel Castro to power.” Yes, the sugar business made a few people rich and killed most of those who produced it – but sugar also changed hearts and minds. Sugar transformed national realities. Sugar birthed ideologies.

By 2004 the Domino Sugar Refinery had closed, joining the ranks of abandoned and desolate warehouses and factories that dotted the Brooklyn coast. Relics of a former age. Today, the grounds around the refinery have been turned into a park – complete with volleyball courts, a taco stand, and a playground utilizing shapes and materials evocative of the industry that once occurred here. The refinery building itself is now filled with offices, a building that “melds history, innovative engineering, and sustainability for the 21st century.”

New York City is constantly changing. Anyone who has lived here long enough knows that, and can probably reminisce about a handful of establishments they used to frequent that have sadly shuttered. In the grand scheme of Gotham’s continuous death and rebirth, I’m not mad at the bougie offices or the pristine park that have taken over the Havemeyer’s former domain. At least a nod to the past was preserved. But I suppose history and preservation are cool now. Who knows what will become of the building in another century.

Sometimes when I see the Domino Sugar sign I think of the sugar packets, crammed into little black containers, sitting on diner tables across the country. Sometimes, I think of sweets made at home and the worn paper box that would be pulled from the cupboard shelf for its making. When I’m walking around Domino Park, I often think about how much Williamsburg has changed — how a friend and I once spent a teenage summer afternoon photographing the abandoned waterfront (where Smorgasburg now takes place every Saturday). But most of the time, when I see the yellow script, I think back to being on that boat speeding across the East River, clutching my seat, hair blowing across my face in the wind, ready for an adventure.

Edible History is a reader supported newsletter. To support my work and to gain access to the full archive of posts (each month paid subscribers receive additional edible histories and recipes in their inbox) consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber.