The Cracker

An edible history.

Question time. How often do you eat crackers? How often do you specifically crave a cracker? Really, how often do you even think about crackers?

Personally, my cracker consumption largely involves using it as a vehicle for cheese. Often when I come home from work, hungry and in need of an immediate snack, I get a box of crackers from the cupboard, a hunk of cheese (whatever is in the fridge will do) and proceed to shovel bites of cracker and cheese into my mouth as I stand at the kitchen counter in silence, staring into space, contemplating the events of my day. Once I’ve absorbed enough calories to face the evening tasks, the crackers return to their shelf in the cupboard and I don’t think about them until the next evening. Out of sight, out of mind.

Crackers are a functional snack. In fact, the only cracker I think I have ever specifically craved are Cheez-its. I love Cheez-its. They were my favorite snack as a child, and the only reason they do not take pride of place in my cupboard (where my healthier adult crackers now reside) is because I could consume (and have) ungodly amounts of those sodium packed cheesy bites.

Perhaps today the cracker mainly exists as a vehicle for other foods – but in the past they provided critical sustenance and even formed the basis of some people’s diets.

Starting in the late 15th century, seafaring vessels began to make incredibly long voyages. Ships would go months without coming to shore, as Europeans began their violent subjugation (or “exploration” as outdated historical narratives will tell you) of the entire globe. When a ship left port, of course it would be packed with food — but in a time when maps were still being drawn, and ports controlled by other Europeans (where supplies and fuel were guaranteed) had yet to be established – food at some point, would either run out or go bad.

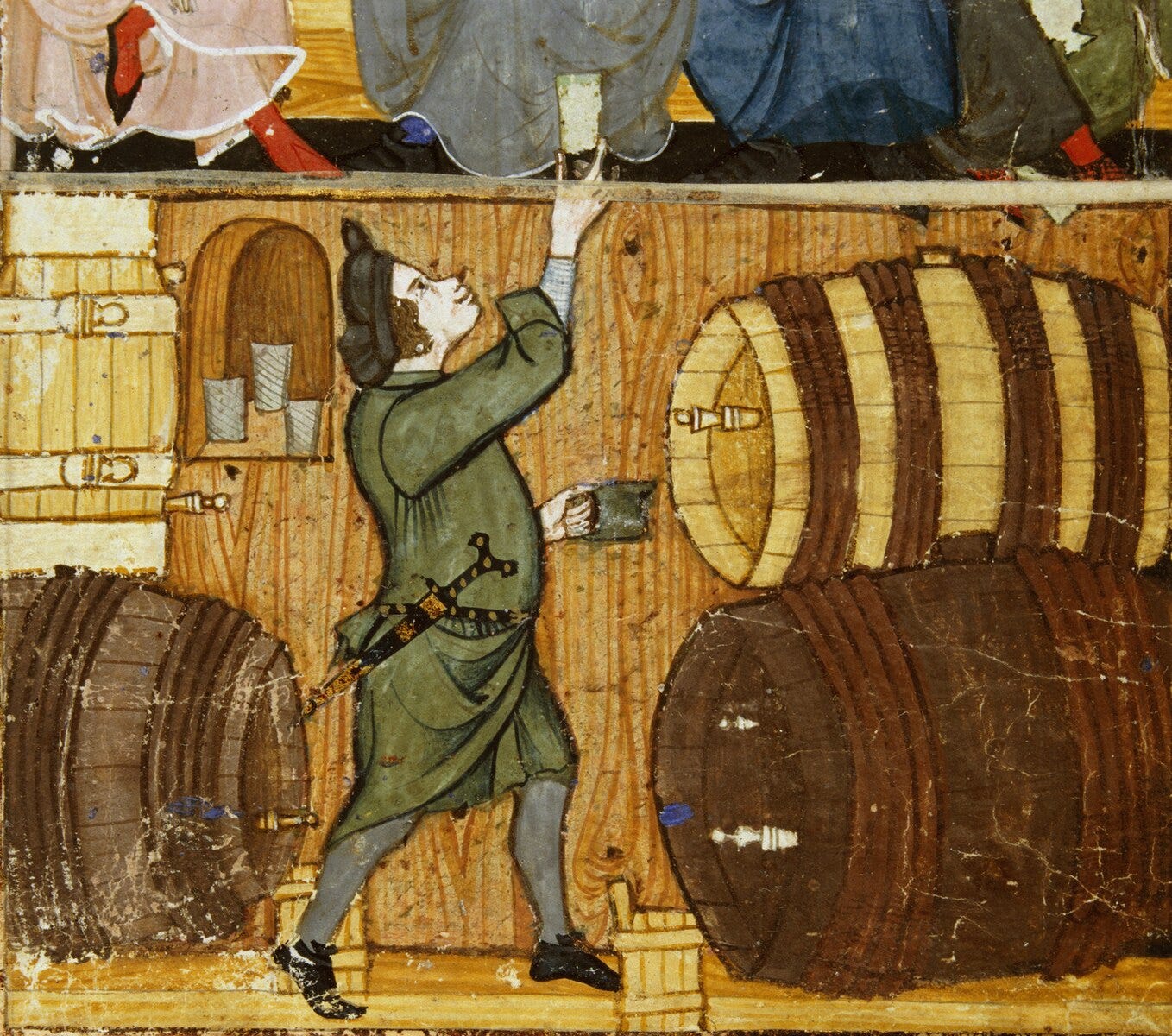

Creative edible solutions were devised. India Pale Ales, or IPAs, were created for British sailors making the trek from the British Isles to India. By adding large amounts of hops to the beer, sailors found it could last months, even years, without spoiling (think about that next time you order an IPA at the bar!)

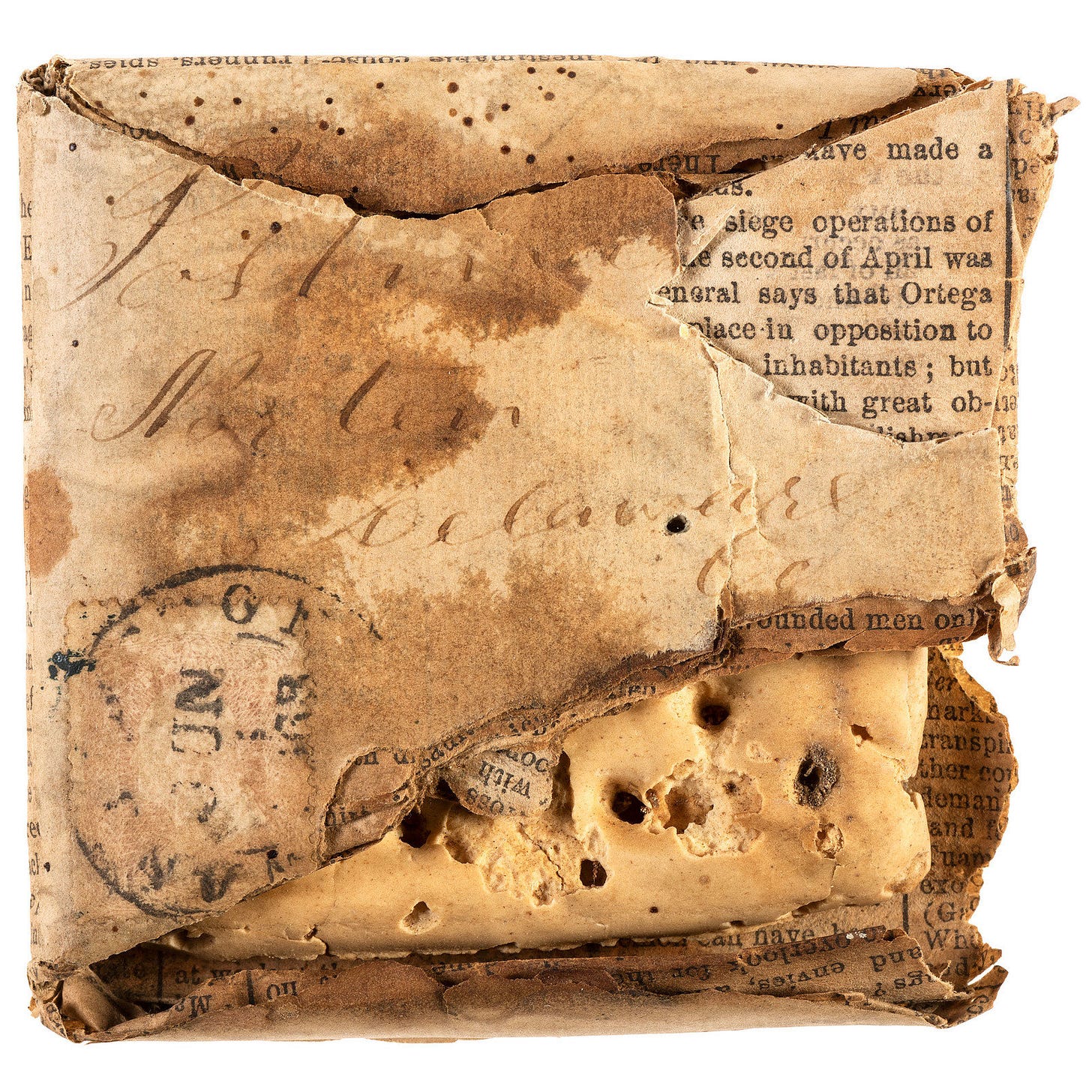

And then there was hardtack. The original cracker. A cracker so dense, so tough, so devoid of all gustatory pleasure that it literally never went bad. Hardtack was made with flour and water (sometimes a little salt) and was baked multiple times to create a durable cracker that could survive all kinds of climates and last years on board a ship. It was so hard that it had to be soaked in liquid to be consumed. Biting straight into hardtack would break your teeth.

Hardtack became a standard ration for sailors in the British Navy in the heyday of that nation’s enormous empire. It was Samuel Pepys, an administrator in the Royal Navy who standardized the sailor’s daily diet to include, in addition to salt pork and beer, a pound of hardtack a day. (Pepys, aside from his cracker legacy, also kept a very detailed diary in the 1660s that is a treasure trove of information on daily life in this period).

However, hardtack, or ship’s biscuit as it was also called, is much older than the British Empire. Throughout history, the maintenance of an empire has been inextricably linked to the maintenance of its military – and more crucially, the effective nourishment of that military. Afterall, what can a hungry army accomplish?

In ancient times, Roman soldiers were issued a twice baked bread called bucellatum as a field ration, while Egyptian sailors had dhourra, made from sorghum. The Inca managed to amass the largest land empire ever seen in the Americas, largely because of non-perishable and easily transportable meals in the form of chuno, which isn’t a cracker, but you get the idea. Food that does not perish allows humans to accomplish extraordinary things. Just look at the freeze-dried meals we send astronauts into space with (I’m sure a medieval sailor would have killed for some freeze-dried ice cream).

In the 19th and early 20th centuries commercial crackers entered the fold, mainly because of industrialization and the new ability to mass produce crackers in factories. It’s quite amazing how many of these early cracker brands and varieties we still know and eat today: saltines, graham crackers, oyster crackers, Ritz crackers, Triscuits, Cheez-Its, Carr’s, animal crackers, the list goes on.

As the cracker entered the American home, its makeover from nautical survival food to pantry staple was complete. From big cities to small country towns, the cracker in all its regional varieties became as common as bread — with the added bonus that it lasted a lot longer. Crackers were served with dips, cheese, or slices of cured meat at social gathers. Graham crackers were crumbled into a fine texture and made into cheesecake crust. At country stores throughout the American south, barrels of soda crackers were shipped in to be bought by the pound, the barrels themselves serving as makeshift tables around which neighbors would chit chat and exchange local gossip. It was around this time that “cracker” also became a racial epithet for white people.

Perhaps crackers are a rather mundane snack food in the grand scheme of edible history. But like any food, there is real history there.

The next time you pull a box of crackers off the shelf, transport yourself for a moment to the 16th century. To the southern Indian ocean. On board the deck of a carrack. You are standing in the hot midday sun, surrounded by a group of sunburnt and scurvy ridden European sailors who have eaten nothing but hardtack for weeks. Now imagine telling them that 500 years into the future, people on dry land would be consuming crackers as a fun little snack.

It might just be enough to make them jump overboard.

This the free version of my newsletter. If you would like access to the full range of posts published each month consider upgrading to a paid account or a gift subscription for a friend!

I love crab dip and crackers and there's nothing better than cheez-its in tomato soup.

In 18th & 19th century Wales children used to beg ship's biscuits from returning sailors, to be taken home and baked in milk and butter as a treat - there's a mention of it in Susan Cooper's book 'Silver on the Tree'. Interesting to hear about all the American cracker types, too - although we do of course have crackers in the UK I feel like they occupy less of a space in the food landscape over here.