“He was a bold man that first ate an oyster.” - Jonathan Swift, 1738Let’s be frank. One does not necessarily look at an oyster and think, “That looks delicious.” But for as long as I can remember, I have loved them.

One of my earliest oyster memories is eating them by the port in Sète with my father when I was very small. My father is from Nice, and so many summers of my childhood were spent in the south with my French family. At some point he must have introduced me to the mollusks, found that I enjoyed them, and delighted by his daughter’s adventurous eating habits made a point of bringing me to oyster bars with him – where we would down them raw with lemon juice on the half shell, ordering dozens each, until we couldn’t possibly eat one more. (You have to eat a lot of oysters to become full.) To this day, gorging rather alarming quantities of oysters together is one of our most sacred rituals.

In the 2010s, the heyday of $1 oyster happy hour deals across New York City, I spent a rather strange and stressful year working for a boutique PR firm in Chelsea. A few evenings a week, I would find myself courting some journalist or blogger over a dozen oysters and well drinks at one of the restaurants we represented. Sometimes the oysters were from Maine, with deep cups that still held seawater. Sometimes they were the New England classic Wellfleets, with soft ridged shells and a hint of sweetness. But most of the time they were local Blue Points, straight from the Great South Bay of Long Island.

For me, oysters and New York City are intertwined. And this isn’t because I’m a New Yorker who loves oysters. It’s because oysters are written into the DNA of this city’s gastronomic history.

The waters around the shores of lower Manhattan, Brooklyn and Staten Island once contained half of the world’s oyster population. Billions of them carpeted the seabed. Not surprisingly, they were a natural food source for the Lenape, the people indigenous to this land, and we can find traces of their pre-European consumption in the oyster middens that lie below high-rises and sometimes emerge at construction sites.

When Europeans began to arrive in the 16th century, settlers wrote of the bountiful waters, teeming with life. There were hundreds of different kinds of fish. There were dolphins, whales, and porpoises. And there were oysters – some apparently as big as a baby (even I can admit that’s a rather terrifying prospect).

As the merchant trading town of New Amsterdam grew into the booming port city of New York, oysters provided critical calories to the growing metropolis: they were cheap, they were nutritious, and they were seemingly limitless.

In the 1790s, the West Indian traveler Médéric Moreau de St. Méry visited the city and was quite taken with how many oysters were consumed by its residents. He wrote, “Americans have a passion for oysters, which they eat at all hours, even in the streets. They are exposed in open containers in their own liquor and are sold by the dozens and hundreds up to ten o’clock at night in the streets, where they are peddled on barrows to the accompaniment of mournful cries.”

Indeed, oysters reigned supreme in 18th and 19th century Gotham. Oyster carts would park themselves outside factories, selling oysters for pennies a piece to hungry laborers. The city’s taverns would serve them roasted in stews and pies. And in 1763, in a basement on Broad Street, the city’s first oyster cellar emerged. These cellars ran the gamut from grimy hole-in-the-wall to refined eatery with crystal and silver spoons – but they all served the ubiquitous mollusk, “in every style.”

Some oyster cellars were marked by a red balloon, the traditional sign of a brothel, and indulged their customers in the famed aphrodisiac qualities of the oyster. Other cellars offered the “Canal Street Plan,” all you can eat oysters for a mere six cents. George Makepeace Towel (what a name!), a British visitor to New York in the 19th century wrote, “There is scarcely a square without several oyster-saloons; they are aboveground and underground, in shanties and palaces. They are served in every imaginable style, escalloped, steamed, stewed, roasted, ‘on the half shell,’ eaten raw with pepper and salt, devilled, baked in crumbs, cooked in pâtés —” and, well you get the picture.

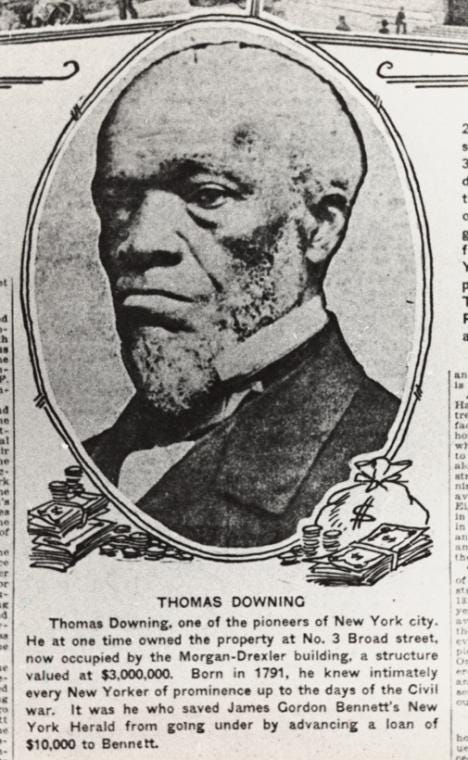

One cannot talk about oysters and New York, without talking about Thomas Downing. Born to a free Black family in 1791 near the Chesapeake Bay, Downing moved to New York in 1819. He lived at 33 Pell Street with his wife and bought a small skiff that he rowed out across the Hudson every morning to pick oysters. A decade later he had enough customers, and enough capital, to open his eponymous oyster cellar at 5 Broad Street.

Downing’s luxurious dining room quickly became a hub for businessmen to slurp oysters and talk shop. Mayor Philip Hone referred to him as, “The great man of oysters.” When the city of New York threw a ball in honor of Charles Dickens’ 1842 visit, Downing catered the event. Downing himself became known as the man who knew all the secrets of City Hall and Wall Street. And he had secrets of his own – unbeknownst to the largely white, generally wealthy crowd of patrons above, the basement of Downing’s formed a stop on the Underground Railroad, hiding enslaved people on their way to Canada.

By the early 20th century, the waters around New York had become so polluted with runoff from factories and contaminated with sewage, that oysters sourced from its immediate environs were deemed unsafe to eat. The oysters that had once helped to sustain the city, were destroyed by Gotham’s growth. As oysters had to be shipped in from further and further away, they became more expensive. Gone were the days of oysters for all. The mollusk became a delicacy for the 1% and the masses found other cheap foods to consume.

In his book, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, Mark Kurlansky writes that New Yorkers have lost their connection to the water. And maybe we have. How often do we as New Yorkers think about our proximity to the sea? We live upon rivers, estuaries, bays, and beaches. We live on piles of earth that cover up ponds, canals, lakes, and marshes – once teeming with life.

Today the Billion Oyster Project, is taking on the heroic initiative of planting oysters along the shores of the city, in the hopes of restoring our waterways to their former glory. Turns out clean water is good water – and also that all those oysters created a natural seawall that provided protection against storm surges – something the city desperately needs as we face rising sea levels and storms that upend our delicate infrastructure.

A few weekends ago, I was strolling around my neighborhood on a chilly but sunny Sunday. The water has become a much bigger presence in my life since I moved to Red Hook (Kurlansky, I have remembered!) I looked out at the lines of barges waiting to unload across the river. Ice covered the rocks along the shore. Some ducks were bobbing around in the shallows undeterred by the frigid temperatures – or the trash floating nearby. I thought about what kinds of oysters must have grown here a few hundred years ago, and what they might have tasted like.

I was hungry. Hungry for oysters. I walk inland a couple blocks to Brooklyn Crab, a ramshackle wooden seafood spot that looks like it was plucked out of a coastal New England town and plopped down in Brooklyn. I walk up the stairs to the bar and order a dozen oysters, $1 a piece on Sundays. Here I spend some time, squeezing lemon on briny mouthfuls. Each one, delicious nostalgia – with a good dose of local history too.