How did one single flower come to be the universal symbol for love? Of all the flowers, why the rose?

The rose is objectively beautiful (if I may be so bold). It’s hard not to look at the red rose my friend Sonia grew in her garden, and not be in awe that nature could produce something so lovely (though to Sonia’s credit, she is literally a professional florist). I suppose love is a beautiful thing as well – though the thorns of the rose will remind us of its potential for pain.

A rose is not whimsical like a tulip, or delicate like an iris, nor dainty like a buttercup. There is something about the shape of the rose that makes it majestic. There is a quiet strength in its regal nature. A single rose can shine on its own. Perhaps these are qualities that make us equate it with love. And on some subconscious primordial level, throughout most of history, humanity has agreed with these sentiments.

The famous Scottish poet Robert Burns wrote that, “My love is like a red, red rose.” In The Little Prince, the Prince learns about love from his rose. Shakespeare’s Juliet proclaims to Romeo that, "A rose by any other name would smell as sweet." In the Disney classic, The Beauty and The Beast, the life of an enchanted rose determines fate; destined to wilt and slowly die and condemn the Beast to a life trapped in monstrous form – unless he can learn to love.

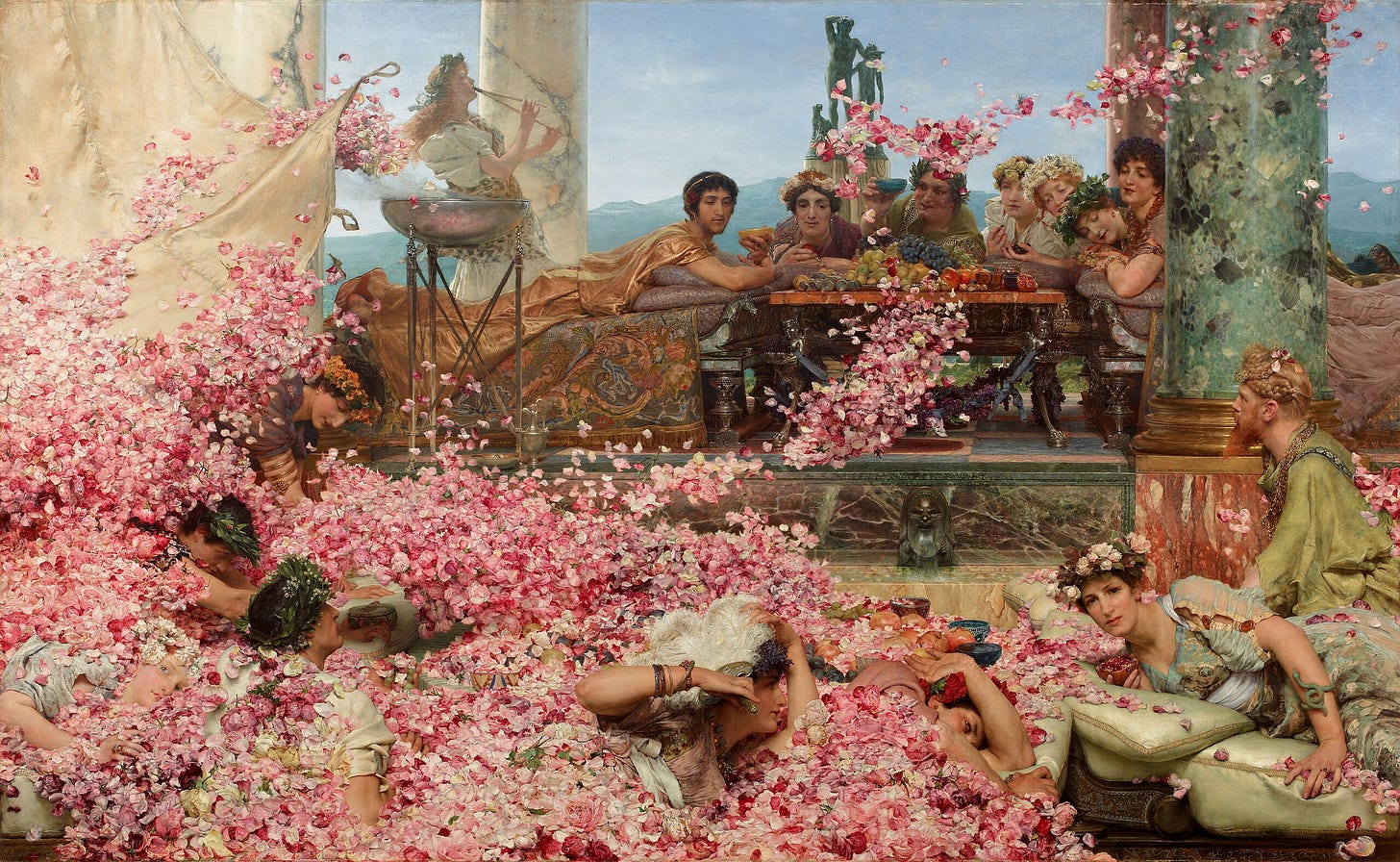

The symbol of the Tudor dynasty was the rose. The White House famously contains a Rose Garden (though Melania Trump did a fantastic job making it as sterile as possible, prompting one Twitter user to remark, “If you don’t like what the Trumps have done to the Rose Garden, wait till you see what they’ve done to the Constitution”). Earlier fascists, like the Roman Emperor Elagabalus, once held a banquet in which he had an avalanche of rose petals fall from the ceiling. The weight of the roses was so great, that the petals crushed and suffocated his guests to death (now that’s a big flower budget). Today, the red rose is also a symbol of socialism. On social media, the red rose emoji is often used as a nod to socialist beliefs. Coincidentally, an emoji Brittney Spears uses frequently, prompting some fans to speculate that she is in fact a socialist (get it comrade, Brit).

Van Gogh painted roses. Marie Antoinette posed for a portrait with a rose. Salvador Dali painted a meditative rose. We give roses to those we love on holidays like Valentine’s Day – or just because. The famous adage, “Stop and smell the roses,” reminds us to slow down and see the beauty in every day.

The rose is everywhere. In film, in literature, in art, in music – even in politics. We don’t often find the rose in the kitchen – at least not as an ingredient. But that doesn’t mean the rose has not featured in recipes throughout the ages.

The first century Roman cookbook Apicius, features a recipe for Patina de Rosis, or baked brains of roses. Yum. The recipe calls for boiled calf or pig’s brains to be combined with eggs, rose water, garum, wine, and black pepper. The dish is then baked in the fire’s embers and decorated with rose petals. While a number of Apicius recipes made their way into my book, this is not an ancient recipe I will be trying.

In the 10th century Baghdadi cookbook, The Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens, Ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq provides the reader with recipes for rose syrup. The syrup may be drizzled over pastries, nuts and dried fruit. In the 15th century Italian cookbook, The Art of Cooking, by Maestro Martino, we find a recipe for a Cherry and Rose Petal Torte, spiced with cinnamon, ginger and black pepper.

Recently, I finished Jill Burke’s How to Be A Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity. It’s a real feat of primary source research. Burke has recovered the lives of countless women from Renaissance Italy – including gay and trans women, who are typically nonexistent in the historical record. While Burke’s work does not include recipes for cooking with roses, it does include a number of recipes for making beauty products with roses.

One of Burke’s main sources is Giovanni Marinello’s The Ornaments of Ladies, published in Venice in 1562 and filled with over 1,400 recipes for beauty products. There are recipes for ointments, scrubs, scented waters, tonics, lotions, lip balms and anti-wrinkle creams. Marinello says of her own recipe for a rose and bran body scrub, “You will not find anything better to wash your body.” Another recipe for a rose lip balm promises to, “heal the lips excellently,” while the application of her lavender, rose and sage water, “consoles the spirit and puts you in a good mood.”

Food history is not just about taste – it also involves smell and touch and sight. To make Marinello’s rose and bran scrub, we can feel with our hands the coarseness of the oat bran. We can carefully add droplets of rose water to the mixture. We can tend to our own careful little concoction – and then rub it all over our bodies. We can experience the same scents and textures Marinello would have 462 years ago. Across time, we can share a moment with her. We can stop and smell the roses – through the centuries.

Like all things, a rose does not last forever. Eventually, a rose will wither and die. And then the rose becomes a memory. And in that sense, the rose really is an apt symbol for love. Something beautiful. Something ephemeral. Something to be cherished as long as it lasts.

Then back to the earth it goes.

Edible History is a reader supported newsletter. To support my work and to gain access to the full archive of posts (each month paid subscribers receive additional edible histories and recipes in their inbox) consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber.