The Tomato, part 1

An edible history of its origins.

You guys, we did it. We have finally made it to one of the most glorious times of the produce calendar – it’s tomato season.

Ripe and ready at the market are classics like the Roma tomato, Celebrity tomato, the Early Girl tomato, and the San Marzano tomato – all excellent for using in salads, sandwiches, and sauces. There are the heirloom varieties, gnarled and bulbous: the Cherokee Purple, the Black Krim, and the Raf, which when sliced reveal complex interior patterns of flesh and seeds. There are the tie dyed green, yellow and red skins of the Green Zebras and Mr. Stripeys. There are the petite and sweet Cherry and Sungolds. Which of course one could use as a component of a dish – but are equally delightful eaten raw, one by one, popping the skin open between your teeth, an explosion of vermilion candy juice hitting the inside of your cheeks.

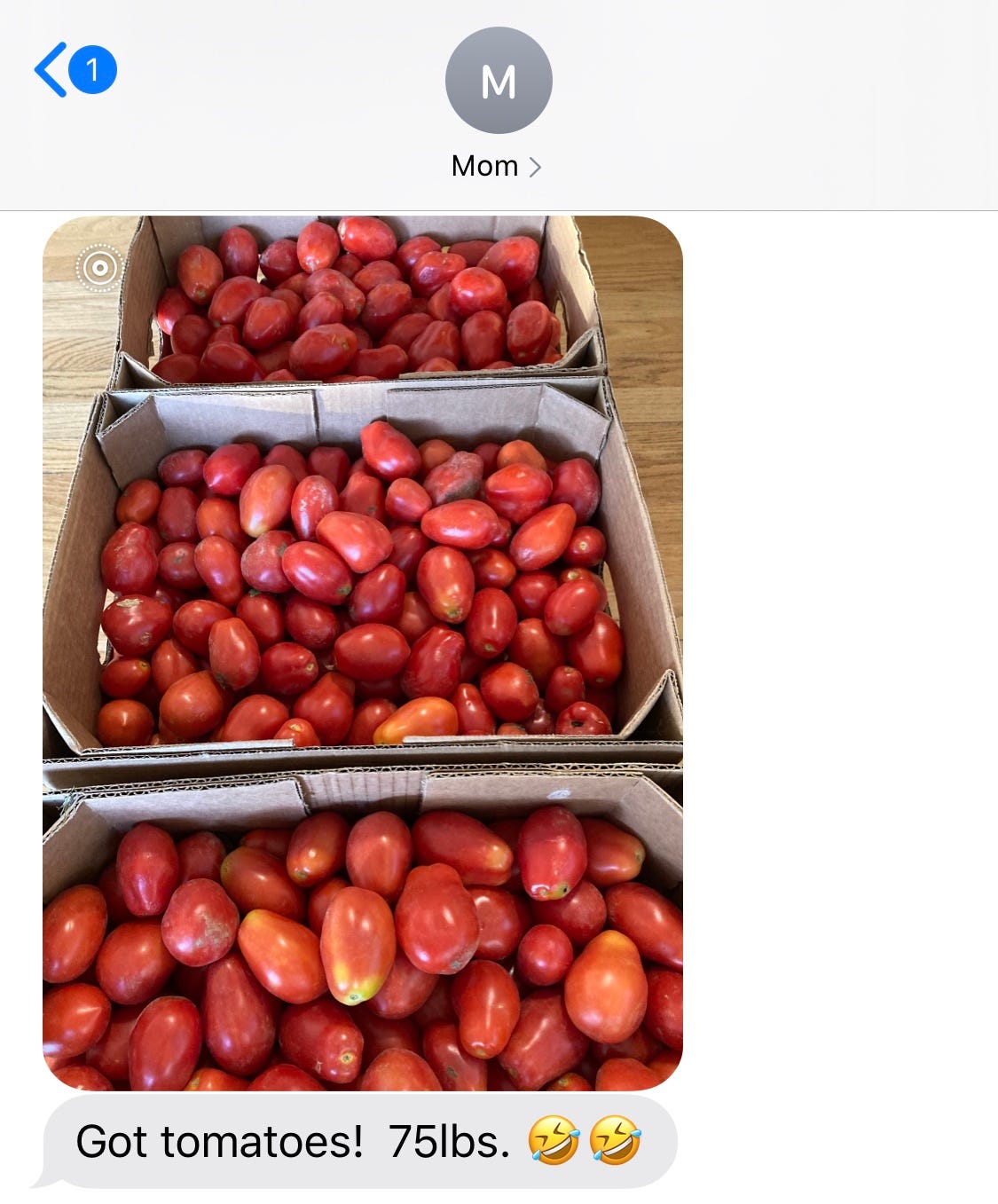

There is no wrong way to enjoy a tomato in peak tomato season. Raw, cooked, blended into a gazpacho – heck, eat one like an apple if you feel called to do so. One of my family's annual summer rituals is to make tomato sauce. A lot of it. Every August, pounds and pounds of tomatoes are purchased, and quickly every pot, pan, and fire proof vessel in the house turns into a simmering, bubbling vat of sauce. The kitchen descends into a tomato juice splattered war zone, as the fruits are boiled, peeled, and then cooked down. Once the sauce is ready, it's ladled out into containers and ziplock bags and stored away in the freezer. Many months later, in the deep dark depths of winter, you can retrieve a pint of sauce and savor for a moment the taste of summer.

Pasta with tomato sauce. A staple dish of Western cuisine. Perhaps we could even consider it to be a kind of global staple? In all my travels, I can’t think of many food shops I have been to – from urban big box chains to rural stores with just a few dusty cans on the shelves – where some kind of pasta and a can of tomato sauce haven’t been present.

Of course we associate the origins of this dish with Italy. We are not wrong to do so. The Italians make damn good tomato sauce. But tomatoes are not Italian. The Solanum lycopersicum plant did not originate in the Mediterranean. The tomato comes from the other side of the world, from the Americas. And it was domesticated by the Aztecs.

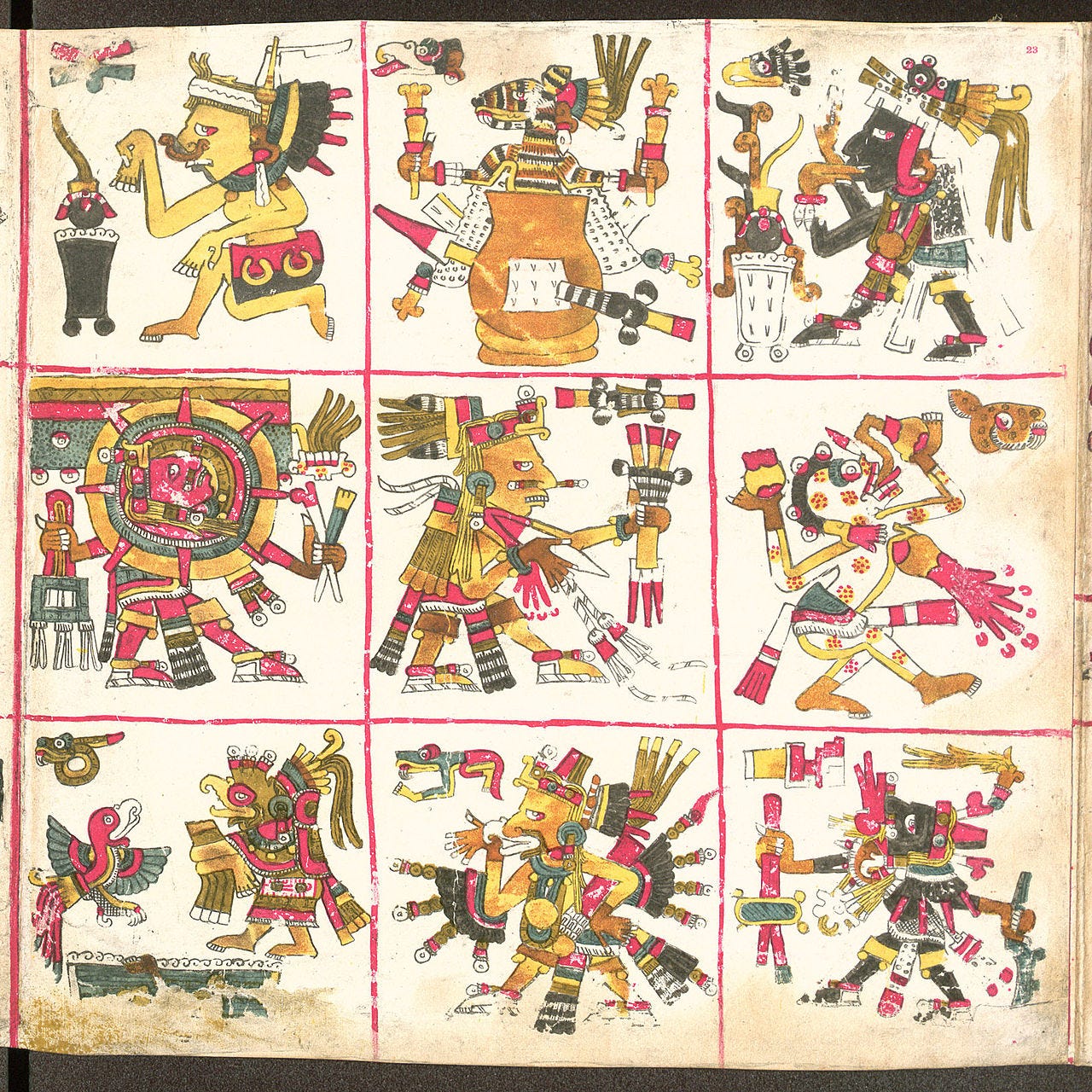

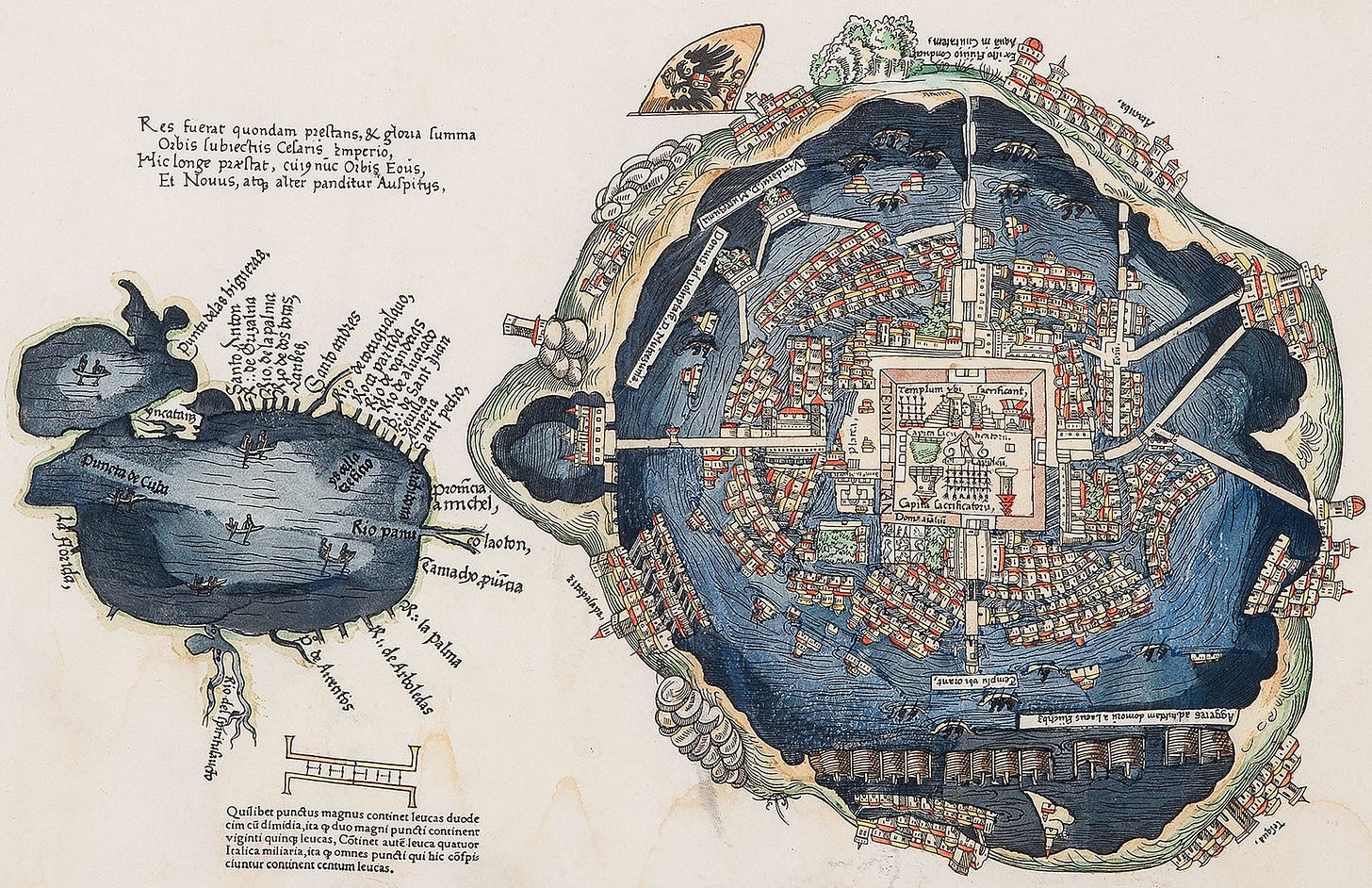

The Aztec Empire, which ruled over central Mexico in the 15th century, was a political alliance between the three most powerful Nahua city-states: Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. At the center of the empire lay its capital city, Tenochtitlan (today Mexico City), which was built upon an island in the middle of a lake. Thousands populated the floating urban center. Tenochtitlan was divided into municipal districts – each with its own local council, temple, and central market square. The capital city also had a library, a zoo, ball courts, palaces and pyramids.

The markets of Tenochtitlan were filled with piles of cacao, bars of dried green algae from the lake, honey, birds eggs, venison, rabbits and frogs. There were prepared foods: premade tortillas, squashes already peeled and cut up for the cook short on time, amaranth cakes, fried onions, and of course, all kinds of sauces – many made from tomatoes.

Most likely, the Aztecs were the first society to domesticate the tomato – though the plant did not originate there. The Andes Mountains in Peru are believed to be the original home of the tomato. The red juicy fruit we are familiar with today would share little in resemblance to its wild, often inedible, ‘thumbtack’-sized forbearer. Botanists have yet to understand exactly how this tiny plant traveled thousands of miles north to Mexico, where it was transformed into the edible fruit we know today – but somehow it did.

The most well known Aztec ruler is, of course, Montezuma. He assumed the throne in 1502 and led the Aztecs to the apex of their power. He established a strong centralized government with a highly organized bureaucracy. He restricted the power of the noble class, and strengthened the military. But then in 1519 the Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes arrived on the east coast of Mexico – and well, things began to fall apart from there.

For a long time the history books have painted Montezuma as weak: outmatched by the horses and weapons of the Spanish. Chronicles recount him simply crumbling in the face of a much stronger foe, and handing over the city like some sort of Boabdil. But we have forgotten that the Spanish had made alliances with other indigenous peoples, like the Tlaxcala, who were sworn enemies of the Aztecs. Between this alliance, the knowledge of locals from people like the truly fascinating Malintzin – it wasn’t weakness, it was unbeatable odds (and that’s not even getting into the germs and disease).

As Spain dug its hooks into the New World, parts of this land made its way to the old one. We don’t know their name, but at some point as a ship was being loaded with goods of the Americas, someone took it upon themselves to bring a small tomato plant aboard. From here, the plant would sail through the Caribbean, across the Atlantic and into an Iberian port.

Commodity extraction involves unthinkable horrors. Millions of indigenous decimated, entire civilizations wiped out, centuries old cultures, languages and traditions erased. But the Swiss naturalist Konrad Gessner likely wasn’t thinking about all this when in 1554 he described the tomato plant as poma amoris, or love apples.

When the tomato was first introduced to Europe it was grown mainly as a decorative plant; Europeans remained undecided as to whether it was poisonous or some kind of aphrodisiac. But this attitude would slowly change. The tomato was about to be assimilated into a whole new culinary identity.

There’s still time to place orders for the Edible History X MackBecks jewelry collaboration! Oyster bolos, pineapple pinsand Anthora coffee cups inspired by this newsletter are all available here 🍍🦪☕️

Like what you’re reading? Get a copy of my book, A History of The World in Ten Dinners (Rizzoli) available here and here.

Edible History is a reader supported newsletter. To support my work and to gain access to the full archive of posts (each month paid subscribers receive additional edible histories and recipes in their inbox) consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber.

Love this! I have been writing about the history of ingredients for years, and it's so interesting how identitary some ingredients have become to a certaint part of the world while being originally from somewhere else completely different!