This post is part of the New York City Icons series. Past posts have covered the hot dog, the cup of coffee, Mister Softee, and the Domino Sugary Refinery. Today, we’re looking at rats.

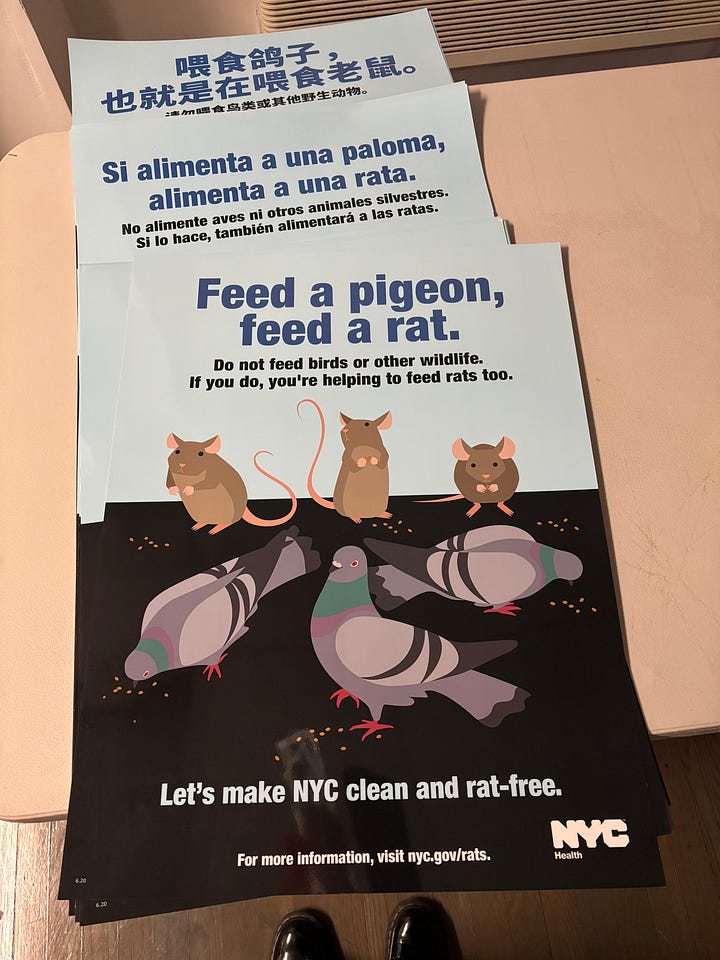

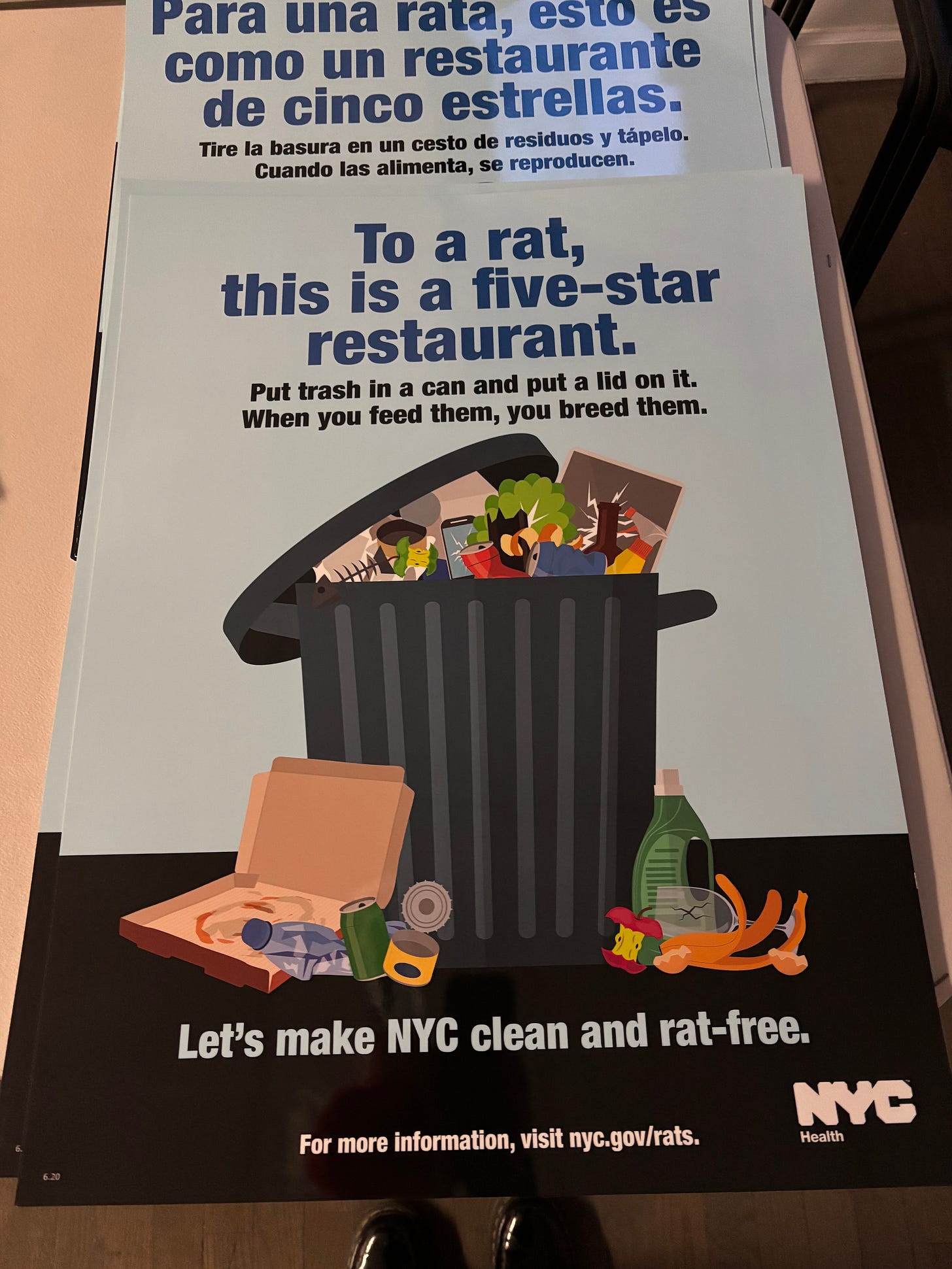

A few weeks ago, on a bitterly cold Thursday evening, I hunkered down in the rec room of an apartment tower block in Harlem with a few dozen of my fellow New Yorkers. We were here for a training session to become members of the Rat Pack – a government sponsored “elite squad of dedicated anti-rat activists.” Part of the training required to become a member of this civilian defence force is a two hour Rat Academy training session. As people shed their layers, grabbed flyers and various anti-rodent educational materials, I opened my notebook and unsheathed my pen. The lights dimmed. The Powerpoint began.

Leading this evening’s seminar was Martha Vernazza, the community coordinator for the New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene. She began by making sure everyone had their raffle tickets, which we were given when we signed in. As if on queue, five of her colleagues wheeled in brand new shiny plastic trash bins (replete with lids), the evening’s prize for raffle winners. These are the same trash bins that were unveiled last summer by Mayor Eric Adams, with all his usual ridiculous bravado, after a $1 million study was conducted to discover that trash bins are more effective when they have lids.

But I’m getting ahead of myself here – perhaps I should explain how I wound up at the Rat Academy in the first place.

This past December at a holiday party, I found myself in the kitchen talking to a woman named Margo about rats. I’m not quite sure how we wound up talking about rodents, but Margo has since said, “I talk about the rats all the time.” Margo was telling me about how a pack of rats had eaten her car battery, and finding herself rat-icalized she decided to join the Rat Pack (I have found many members of the Rat Pack have their own unique rat horror story that served to raticalize them). Margo had recently completed her first training session with the Rat Czar herself, Kathleen Corradi (yes New York City has a Rat Czar, and yes sometimes New York City does not feel like a real place). Margo and I exchanged information. I needed to know more about the Rat Pack.

A few of us from the holiday party began texting about rats the next day. Turns out we New Yorkers have a lot to say about rats. When I asked Margo what the Rat Pack actually does, she responded “I’ll be honest, I have no idea…but I’m not above any anti-rat task.” One thing led to another, and before I knew it I was attending a Rat Academy training session with her.

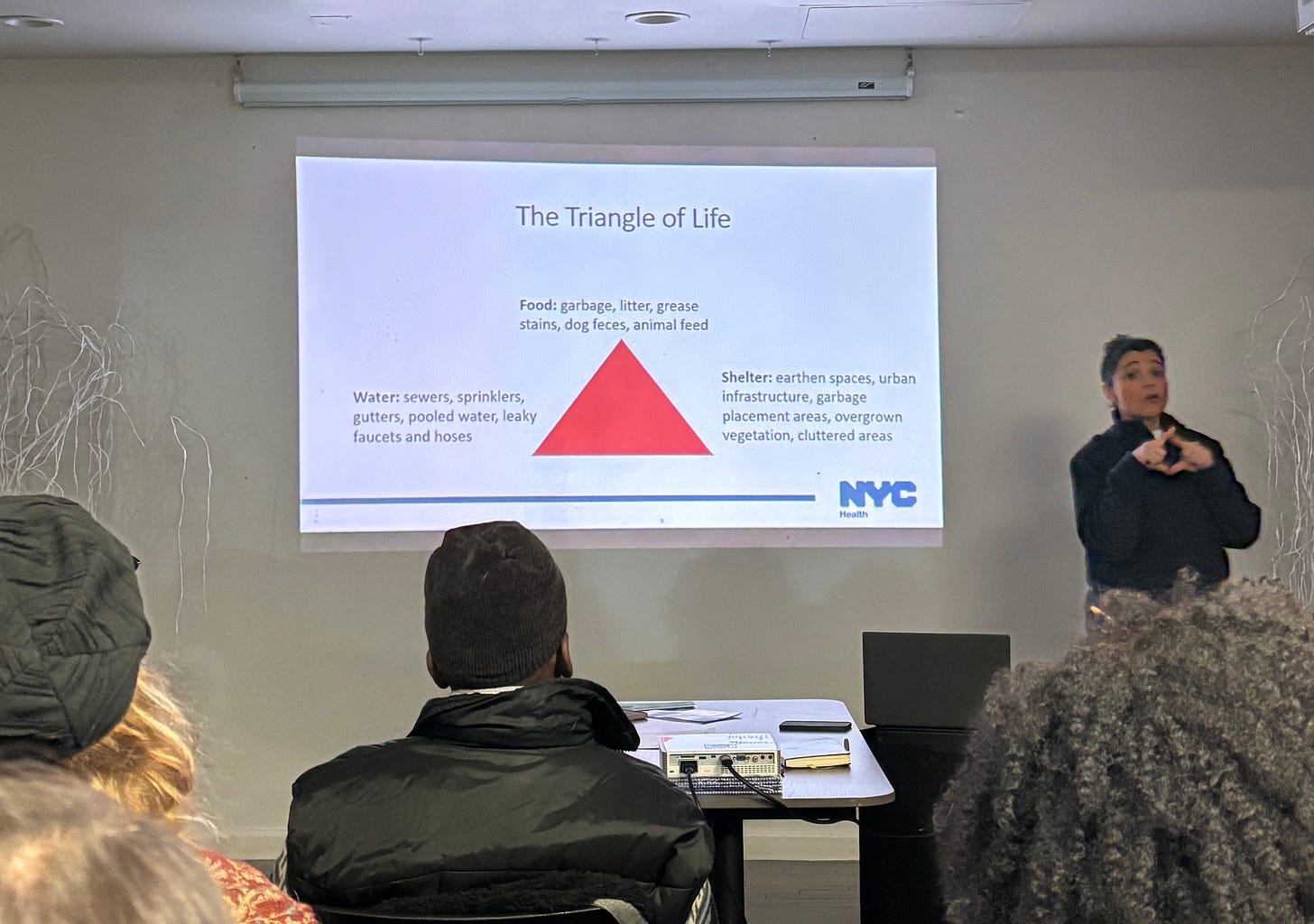

There are an estimated 3 million rats in New York City. The Big Apple can proudly boast one of the highest rat populations in the United States. But what makes New York such an appealing home to rats? A number of factors: easy access to commercial food waste, ideal habitats like parks, green space, and construction sites. And as Martha told us during the seminar, rats, just like New Yorkers, appreciate an easy commute. Parts of our infrastructure like hollow sidewalks, sewers, cable lines, and building foundations provide the perfect secret passageways for rats to make their way around the city – as they make their daily commutes from their homes to their main sources of food. What are those sources of food you may ask? Whatever we eat.

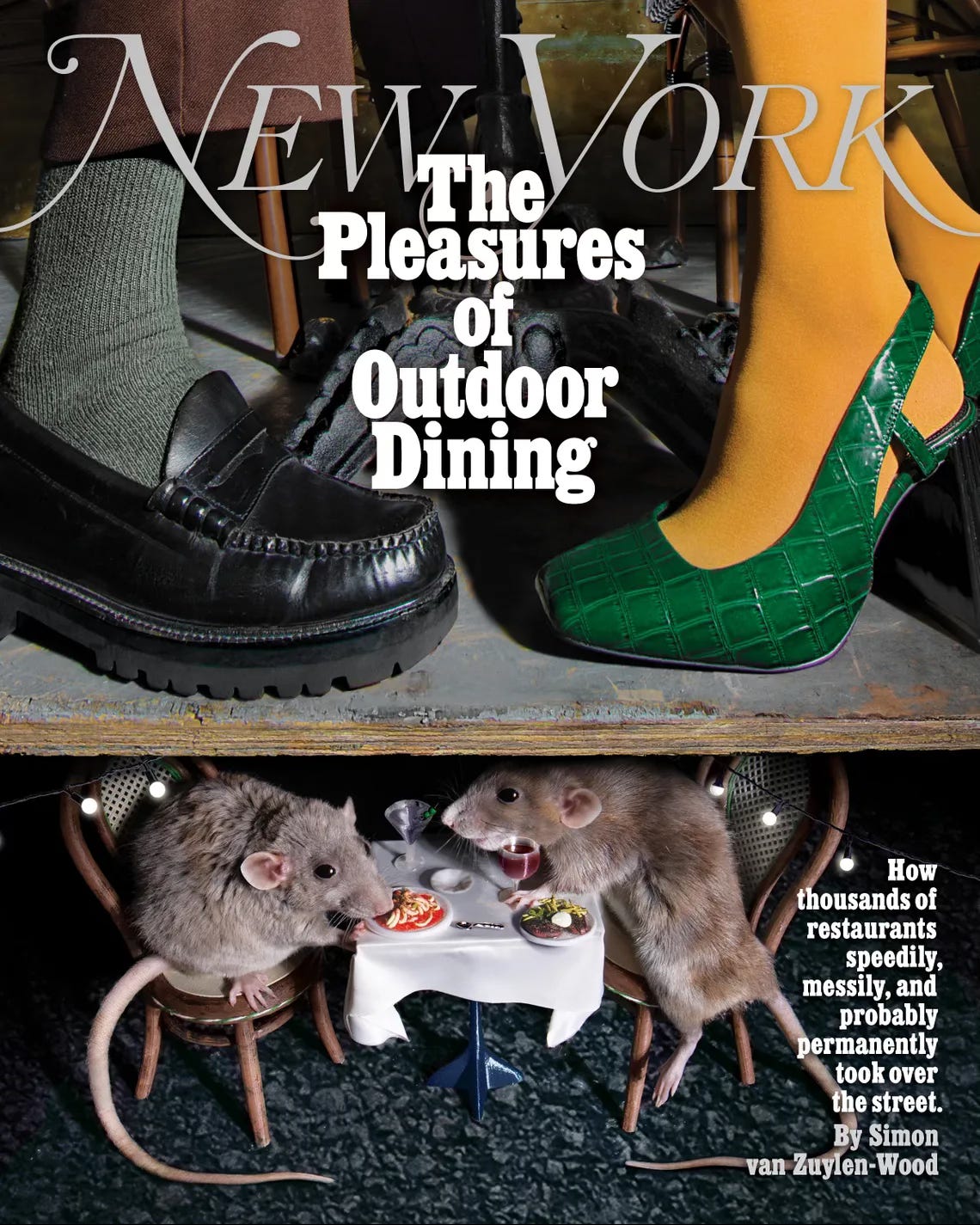

Indesputably, one of the best things about this city is the food. And while restaurants, cafes, bodegas, and food trucks give this city color and life and culture – they also help to maintain a thriving rat population. Outdoor dining was a savior for restaurants (and New Yorker’s mental health) during the Pandemic – but those sidewalk sheds were also, as The New York Times put it, “a permanent picnic for the rats.”

Back at the Rat Academy, Martha told us there is nothing scientifically proven to deter rats. She continued, “When we see rats, we need to stop thinking kill kill kill, and start thinking attack. We need to attack the triangle of life.”

As we began to discuss methods for attacking rat shelters, the subject of tree pits came up (those patches of earth that surround every sidewalk tree in New York City). Tree pits make ideal homes for rats; they burrow in the earth, use found objects like candy wrappers to cover the entrance, and carve out a nice little piece of real estate for themselves. Though aesthetic, the presence of flowers in tree pits actually helps the rats further cover up their underground lairs. One attendee, flustered, raised her hand.

A middle-aged woman wearing big chunky jewelry declared, “I think we can all agree that trees and plants are good and they are not the problem. New York City needs more greenery.”

“Psshhhttt,” a loud huff of disagreement emanated from a large man sitting directly behind her.

“Tree pits ARE the problem!” He yelled. He angrily crossed his arms across his belly.

Another woman in the back row piped in, “I have a question.”

“Yes?” Martha replied, looking slightly exasperated. She was losing the room.

“My landlord is growing vegetables in our backyard. I can see it. And I can see the rats crawling all over the vegetable beds. And our landlord is giving these vegetables to tenants in our building! Is this legal? What can we do to stop him?”

“Um, well I’m not sure there’s really much we can do to stop someone from eating—” Martha was cut off before she could finish.

“What exactly are the laws about killing rats?” All of our eyes quickly darted back to the large man as he spoke,

“Listen, I've lived on the same block for 60 years, and back in the day when I was a kid there was a guy on my block who used to come out every night in the summertime with a baseball bat.” Martha looked nervous. Undeterred he continued. “And he would stand near the trash piles and just start f*cking whacking ‘em! Just killing 'em one by one. And in one night, he could kill up to 20 rats! And he would leave their bodies there in piles, stacked up high…all these dead rats. But then the city came after him!”

A Gen Z Rat Academy attendee stood up to speak on the ethics of rat murder. “Sir, while I support your decision to kill rats, there are 3 million of them in this city. If each one of us got a baseball right now and went outside–”

“3 million and they’re multiplying!” a voice from the left side of the room shouted.

An older gentleman from Bed Stuy chimed in. “Listen this man right here,” he pointed to the loud guy, “is my brother from another mother! He’s asking the right questions! Like is it illegal in New York City to get some steel toed boots on and just starting kicking them up the ******* [description not appropriate for this newsletter] Is that legal?”

“What if the rat is a person?” another man asked the room loudly.

“Oh that’s definitely illegal,” the woman in front of me replied confidently.

I began burying my face in my scarf. I could feel my skin turning as red as rat blood, hot tears welling up in my eyes, as I stifled laughter and thought about how deeply I love New Yorkers. I looked over at Margo – she was laughing so hard she was actually crying. I caught the profile of a young man sitting diagonally across from me – tears were streaming down his cheeks.

Martha attempted to regain control of the chaos triggered by the tree pits. “I will have to send a follow up e-mail about what is and isn’t legal when it comes to killing the rats. But I would like to point out that Community Board 9 has started to test pilot a program for rat birth control.”

The large man raised his hand. With fear and dread in her voice, Martha breathed, “yes?”

“Uh, I don’t actually have a question. I just want to say I think rat birth control is ridiculous.”

Martha sighed. “Look. We are never going to get rid of the rats.”

Nods. Murmurs of agreement as the energy simmered down.

“You’re right,” an older woman behind me said with all sincerity. “Because they have a purpose on this Earth too.”

Ecosystems are a delicate and rather extraordinary thing. Plants, animals, and bacteria all existing together in a carefully constructed balance that has evolved slowly over time. Within these structures, symbiotic relationships can emerge. Take anemone and clownfish. Anemone, a flowerlike marine invertebrate, have stinging tentacles filled with neurotoxins they use to subdue their prey. Somehow, clownfish are immune to this poison, and they use the anemone as shelter to hide from predators. Gracious guests that they are, in return clownfish keep the anemone free of parasites. Nile crocodiles and Egyptian plovers have a similar thing going on. As do zebra and oxpeckers.

Then humans come along. And we don’t really like having things in our environment that make us uncomfortable. Mosquitoes for example. At best, they cause itchy bites and can be a real vibe killer at a summer barbeque. At worst, they carry deadly diseases like malaria. But if we were to kill off all the mosquitoes in a given environment, the consequences would be dire. Food chains would collapse like Jenga – each piece might seem like an innocuous block in the tower, but they are all critical to the structural integrity.

Gotham is an ecosystem of metal and glass and stone. It soars high into the sky with the birds, and dives deep into the earth with the creatures below. Twisting tunnels and pipes cut through the bedrock, and trains shoot around underground at all hours of the day, keeping this whole chaotic concrete jungle vibrating at a low frequency that is matched only by the energy of its people.

Maybe the rat has a part to play in this ecosystem. Sure they can chew through concrete (horrifying). And yeah they are partial to eating car engines because most cars built in America use wiring coated in soy (“A perfect protein meal for rats sheltering from the cold,” Margo has said). But they also eat the fat bergs in our sewers. Surely that must be a good thing. And there’s no denying the role they play in city lore: Pizza Rat forever, Scabby the union labor rat, and recently proposal rat.

As we left the Rat Academy that evening, we stopped at the corner waiting for the light to turn. There, next to a fire hydrant, strewn about the icy sidewalk were torn up bagels. Presumably, someone had put these scraps out for the pigeons to eat (though in this temperature they would sooner break their beaks on them). The real consumer of the half frozen bagel pieces would be none other than the rat. Margo sighed. “If what we’re up against can chew concrete and survive on sewer grease, God help us.”

I guess we’ll just have to learn how to live with them.

Edible History is a reader supported newsletter. To support my work and gain access to the full archive of posts consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber.

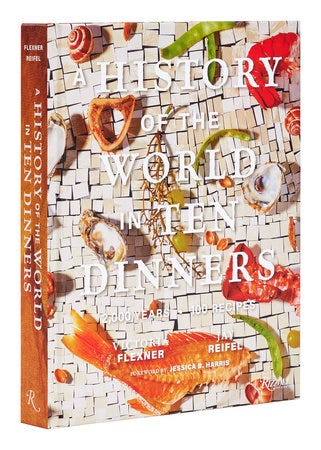

Like what you’re reading? Get a copy of my book, A History of The World in Ten Dinners (Rizzoli) available here and here.

incredible article as always. very effective. finally when you love you count more that's why I continue to say: I love New York!

I had no idea rats were so powerful. Eating concrete and car batteries is WILD!