The Tomato, part 3

An edible history of its mythology: from Sunday Gravy to Eat, Pray, Love, and Honey From a Weed.

All of August I’m writing about the tomato. Its origins in the Americas, its history, its colonization, and its post-1492 life as a symbol of Italian cuisine. You can find part 1 here and part 2 here.

I grew up in New York City’s Little Italy. A neighborhood people visit mostly for its food offerings. There are the Italian restaurants that dot Mott and Mulberry Streets - though these are tourist traps serving overpriced and watered down tomato sauce (for good red sauce, head to Bamonte’s in Williamsburg - Est. 1900!) There are specialty shops selling cheese, meats, fresh pastas and various imported Italian products like Di Palo’s. There are bakeries like Ferrara selling cannolis and sprinkle cookies. When I was very young, I used to put on my best Italian accent for the cashiers at Alleva (RIP) and say hopefully, “Mi piace la bruschetta.” The ladies would coo over my attempts to speak the mother tongue, and as a reward for my little performance, I would receive a big slice of delicious oily bruschetta. Gratuito, naturalmente.

Italians have been present in the United States since the beginning (see Christopher Columbus). But it wasn’t until the late 19th century that they began to arrive in America in huge numbers, most fleeing the crushing poverty of Southern Italy and Sicily. More than 4 million Italians immigrated to America between 1880 and 1924. The tomato, which had become a popular ingredient in Southern Italian food, came with them.

When the tomato was reintroduced to its continent of origin by Italian immigrants, the tomato achieved its final stage of cultural appropriation and transformation: the tomato became a symbol that the rest of the world associated with Italy and Italian food.

Today, Italian food is a principal branch of the American culinary tree. Those red and white checkered tablecloths, wicker bread baskets, and heaping plates of spaghetti and meatballs populate tables across the country. And as Italian Americans have created their own unique version of Italian Italian food, new gastronomic terminology has entered the lexicon: Sunday Gravy (tomato sauce that simmers on the stove top all day, typically Sunday), Muzzarell’ (Mozzarella cheese), Brosciutt’ (Prosciutto). But the thing about Italian American cuisine is that, more often than not, it’s about as Italian as General Tso’s Chicken is Chinese.

While Chicken Parm, Clams Casino, and Penne with Vodka Sauce are all well and good – at some point in the American story of Italian food, it became evident that to experience the truly transcendent properties of this cuisine – and culture – a pilgrimage to the motherland must be made. See: The Godfather, Eat, Pray, Love, Tender Is The Night, The Jersey Shore (Season 4 – a masterpiece from MTV’s reality golden years).

In Eat, Pray, Love Julia Roberts plays Elizabeth Gilbert, a woman in her mid-thirties recovering from a divorce. Post-breakup she finds herself on an international journey of self-discovery, beginning in Italy. In the land of the Romans, she finds herself falling in love with the food – the pizza, the pasta! But Gilbert can’t truly lean into the experience, because of her own indoctrination surrounding diet, weight and the general glorification of thinness. In a scene of emancipation, Gilbert does something radical – she eats a plate of pasta with tomato sauce. By herself. In public. At first she eats carefully, then gleefully, and finally with gusto. She twirls her fork in the durum wheat noodles, slurping rich red sauce flecked with translucent tiny squares of onion, and in doing so liberates herself from the shackles of all that kept her small (thinness, patriarchal constructs of what a woman should be, etc).

And then there is Under The Tuscan Sun (also a book-turned movie). Diane Lane plays Frances Mayes (Lane’s typecast – American divorcée finding herself in Europe) who ends up in one of those ridiculous post-breakup situations: on a ‘Gay & Away’ tour of ‘Romantic Tuscany’ (she is not gay), bumbling through markets in quaint Italian towns, not quite fitting in with the locals or her fellow travelers, when the tour bus randomly stops in front of an old crumbling villa for sale, which she impulsively buys on the spot.

But as Frances settles into her new Italian life, she finds herself facing the same problems that made her leave San Francisco in the first place. She is alone – and she wishes she wasn’t. At Christmas, her local friend Martini gives her a statue of San Lorenzo, the patron saint of cooks, telling her that if she prays to him she might find people to cook for. A few weeks later, the miracle occurs, “Turns out I already had people to cook for. Lots of people to cook for.” Frances begins to cook for the construction crew renovating her villa, her friends, her neighbors – and it is in that act of cooking, with all those heavenly ingredients, that she is set back upon the road towards herself (a hot Italian named Marcello also helps).

What is it about tending to a pot of tomato sauce in Italy that makes it a transformational and semi-religious experience – while cooking dinner at your apartment back home is merely a daily chore?

Let’s consider the recipes in Patience Gray’s 1986 cookbook Honey From A Weed: Fasting and Feasting in Tuscany, Catalonia, The Cyclades and Apulia. I’d argue that this is one of the first cookbooks to present Italian recipes in a starry-eyed and nostalgic way; idealizing rustic peasant life and the good simple food produced from it. Gray, who was a British journalist who abandoned her London life to travel the Mediterranean with her sculptor husband on a ‘marble odyssey’ in the 1960s, wrote, “The recipes in this book belong to an era of food grown for its own sake, not for profit. This era has vanished.” For Gray, the food of Italy is pure, it’s devoid of capitalistic tendencies. She describes how, “Tomatoes are picked at dawn,” cooked in “cauldrons,” and “earthenware vats,” over fires till, “the contents acquire a deeper color and are soft.” She invokes an ancient time before modern kitchens, idealizing the simplicity of hearth cooking, fetishizing the past.

For Gray, and for many other cooks and food writers, Italian food is old. It maintains primordial qualities of cooking from an era when “food was grown for its own sake.” Epicures and civilian cooks alike continue to place Italian cuisine on a gastronomic pedestal, believing that in cooking this food and consuming it we can somehow distance ourselves from highly processed, mass produced junk and return to our primeval culinary roots.

The irony of course, is that there is nothing ancient, or really Italian, about cauldrons of tomato sauce. The whole notion is a fantasy. And perhaps that is why we find comfort in it. Fantasies are comforting. And honestly, why not believe in the magic of the tomato sauce and its soul healing properties? If a trip to Italy can heal your broken heart, God bless.

It’s interesting to think about these national culinary identities that we hold so dear. To examine the cuisines we believe are inherent to certain cultures. I suggest we hold these identities, these cuisines, directly in front of ourselves. Like a perfectly ripe tomato. And then cut them apart to their core. What lies inside? How does the thing break down? I think we might find that each entity is in fact made of many diverse parts. And that most of them are about as real as the myth of Italian tomatoes.

Edible History is a reader supported newsletter. To support my work and to gain access to the full archive of posts (each month paid subscribers receive additional edible histories and recipes in their inbox) consider upgrading to become a paid subscriber.

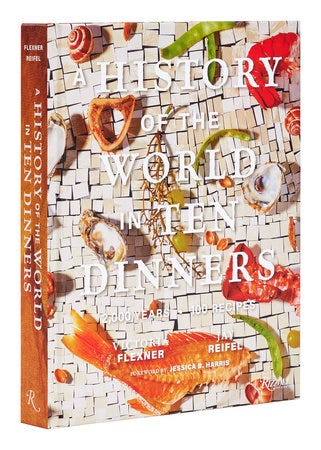

Like what you’re reading? Get a copy of my book, A History of The World in Ten Dinners (Rizzoli) available here and here.

LOVE Bamonte's